What can doctors do that AI can't?

Will AI replace doctors? (Part 2)

Hi everyone,

This week’s email is a continuation of last week’s - a reflection on the role that AI will play in healthcare, and the extent to which doctor’s workflow may become automated.

I have shared the full version (last week’s + this week’s email) on my website here, for those who would rather read it in one go.

Links at the bottom for further articles, on AI in medicine plus other content I’ve shared or come across this week - including a system for keeping in touch with friends and an interview with a podcaster.

Have a great week!

Chris

Some thoughts on whether AI will replace doctors (Part 2)

The challenges of automation

Even in tasks that appear ideal for automation with machine learning, such as ‘pattern recognition’ tasks, things are rarely that simple.

One consideration is that the different decision-making mechanisms that AI algorithms use bring the potential for unforeseen adverse outcomes. For example, while human doctors are trained to be highly aware of rare but serious conditions, an AI algorithm may be less interested if there are few such examples in the training set. Thus an algorithm may appear to perform better than a doctor, by identifying common pathologies with higher accuracy, but may inadvertently perform poorer on the more serious pathologies.

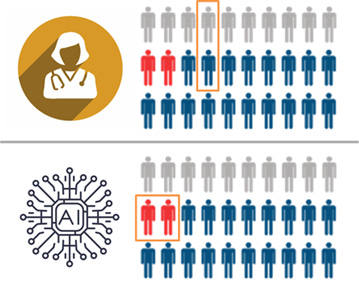

Diagram key: grey = healthy, blue = unwell, red = critically unwell.

In this hypothetical, the human and the AI have the same average performance, but the AI specifically fails to recognise the critically important cases (marked in red). The human makes mistakes in less important cases, which is fairly typical in diagnostic practice.

Credit: Luke Oakden-Rayner

Another challenge is the integration of information from different pattern-recognition tasks. For example, algorithm development for imaging-based tasks often centres around finding the right diagnosis based on appearance. But in a clinical setting, a histopathologist or a radiologist will take into account a variety of other sources of information to come up with a diagnosis and treatment plan. While specialised neural networks (CNNs) may perform well at image classification, an alternative method will be required to incorporate the different sources of information appropriately.

I believe the differences in these approaches may point more towards a collaborative role, with humans and AI algorithms each covering the other’s blind spots. An early example of this is the work automating polyp detection on colonoscopy; the AI isn’t able to perform the procedure, but it is better at detecting polyps of particular shapes.

While such nuances represent technicalities, I believe that with time and intelligent, rigorous methodology to calibrate the algorithms, they can be overcome and, ultimately, will lie within the reaches of AI.

However, there are other tasks which will likely fall outside of its abilities.

The first is what I will call intuitive reasoning. I find this slightly hard to define, but I am referring to instances where we have a sense of a fact, such as a diagnosis, but don’t have a clear rationale of how we came to that conclusion. Perhaps it represents a similar pattern recognition mechanism to AI algorithms, just operating at a level below our conscious awareness. However, I think it’s also possible that it represents a different nature of decision-making which, in particular situations, may be advantageous over AI. Training an AI to replicate this type of reasoning may also be challenging; a lack of self-insight into the variables we used to make a decision may make it harder to determine the appropriate inputs and outputs to a machine learning model.

The second is in the area of social communication, particularly when involving empathy or sensitive discussion topics. Good communication can support doctors in understanding a patient’s problem, and often also forms part of the therapeutic process.

However, the extent to which this is ‘out of reach’ isn’t obvious. Humans excel at detecting subtle non-verbal cues and deciphering nuances in language, but I believe that AI algorithms can also do a pretty good job of this. For example, several studies have looked at diagnosing autism based on video recordings.

I believe the empathetic response evoked by humans is fundamentally different to that evoked by a computer. While this may enable doctors and nurses to bond more with patients, there is some suggestion that people are more willing to share sensitive information with a computer – perhaps given the lack of stigma or fear of social judgement compared to sharing such information with a human.

I think the key area out-of-reach to AI in this domain is the therapeutic role that human interaction can play. As social creatures, albeit in an increasingly digital world, we shouldn’t underestimate how important real human connection can be.

The main impediment to replacement: humans

Before we talk about replacement, we need to actually achieve superior performance and robustly demonstrate this with objective evidence. It’s worth stressing that we’re not there yet - as our study highlighted. But even as technical progress continues, and as AI is shown more robustly to be have comparable or superior performance to humans in an increasing number of specific tasks, I don’t believe that we will allow true ‘replacement’.

We have a different level of acceptance for mistakes by computers than by humans. This has often come up in discussions surrounding self-driving cars; that even if the rate of accidents is significantly lower than from human error, we won’t accept the mistakes. This reflects a wider cultural approach, which it is hard to imagine changing any time soon - particularly in healthcare.

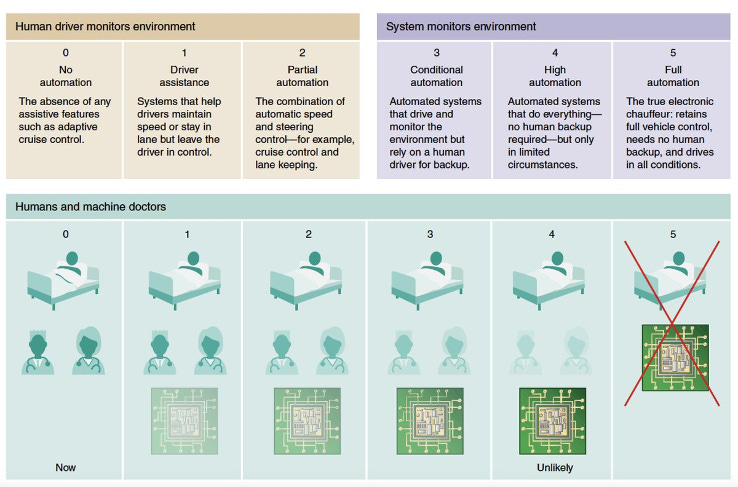

As a result, we will be resistant to giving algorithms too much control. Using the 5-level scale initially featured in self-driving car discussions (diagram below), it is unlikely that we will progress beyond Level 2 or 3 in healthcare – a point made by Eric Topol in Deep Medicine.

Credit: Eric Topol

One risk, however, is that we will decide not to let an algorithm replace a human task, but that it will end up doing so in practice. For example, a tool may be implemented as a ‘decision support tool’ which doctors can use to guide their actions. But if people become very confident in the algorithm, and less confident in their own abilities, the algorithm may de facto automate that decision-making process – despite us deciding we didn’t want it to.

A key aspect will be monitoring performance, as we do with other tools and models that are used in healthcare. However, there are additional challenges of AI algorithms. Performance can change as new data comes in and models are updated. There are also questions around where responsibility lies; if something goes wrong, should you blame the algorithm, or the doctor who says they followed it? Regulation will be a key guiding process in this, but we are yet to figure out how.

An interesting dynamic will occur in poorer countries with lower rates of doctors per population. In some circumstances, rather than AI vs doctor, it will be a question of AI vs no medically trained professional. This makes a stronger argument for affording greater responsibility to the algorithms.

Ultimately though, I believe in the Western world, we will try to draw a hard line in the sand around Level 2-3 of automation, and progression beyond this will face strong resistance – whether it is technically achievable or not.

Conclusion

The limits of what AI can achieve are yet to be known, and will ultimately be borne out with time and scientific investigation. For now, we have the deep learning evolution, from which it is evident that our abilities to process images, and text is much better. The degree of understanding and decision making capability that AI has remains to be seen.

I believe we will see increasing numbers of ML algorithms being developed and used over the next few years – this is already being reflected by an increase in rate of RCTs and FDA approvals. Technical capabilities will expand and we will be keen to implement, but I predict at least one case where an implemented algorithm is later realised to cause harm. This will provide fuel for the argument of a hard cap on responsibility afforded to AI algorithms, which I predict will be around Level 2, with Level 3 for a few specific conditions and scenarios.

Of course, I could be wrong. What do you think?

LINKS

A comprehensive academic review of AI applications in medicine

This is a great review by Eric Topol from 2019, considering the impacts of AI in a wide range of specialties.

A database of social contacts with Monica

After reading this blog post from Derek Sivers a while back, I decided to create a database of everyone I know. I downloaded a platform called Monica and am running it for free on Heroku.

One of my main motivations for this is to have it automatically remind me to keep in touch with friends, as this is something I haven’t always done a great job of. Monica has some pretty cool functionality where you can set up reminders at set intervals for each contact.

(If you want to set up Monika on Heroku but aren’t sure how, feel free to drop a message and I’ll be happy to walk you through it)

Video 1: Will AI replace doctors?

This video is a recording of a presentation I gave at the London.AI meet-up a few weeks back - it’s mostly a summary of our BMJ paper, plus a few thoughts about the role of AI in healthcare.

Video 2: Should I create content? (Episode 2)

Thought about being a content creator (making videos, blogs, podcasts) but not sure if it’s for you? This week I chatted with Mustafa Sultan, who runs the Big Picture Medicine podcast to understand his motivations and experiences of running the podcast.